Early Life

Rosaleen Graves, sister of the WW1 soldier poet and writer Robert Graves, was born in Wimbledon on 7th March 1894. Her father was Alfred Perceval Graves: he was the second son of The Rt. Rev. Charles Graves, Bishop of Limerick. (1846 – 1931). Alfred, who was also a poet, was a school inspector. Rosaleen’s mother was Amalie (‘Amy’) Elizabeth Sophie (or Sophia) von Ranke (1857 – 1951), eldest daughter of Professor Heinrich von Ranke MD, of Munich. Rosaleen’s grandmother was the daughter of Norwegian astronomer Ludwig Tiarks.

Rosaleen Louise Graves, (1894 – 1989) – British WW1 poet and VAD nurse.

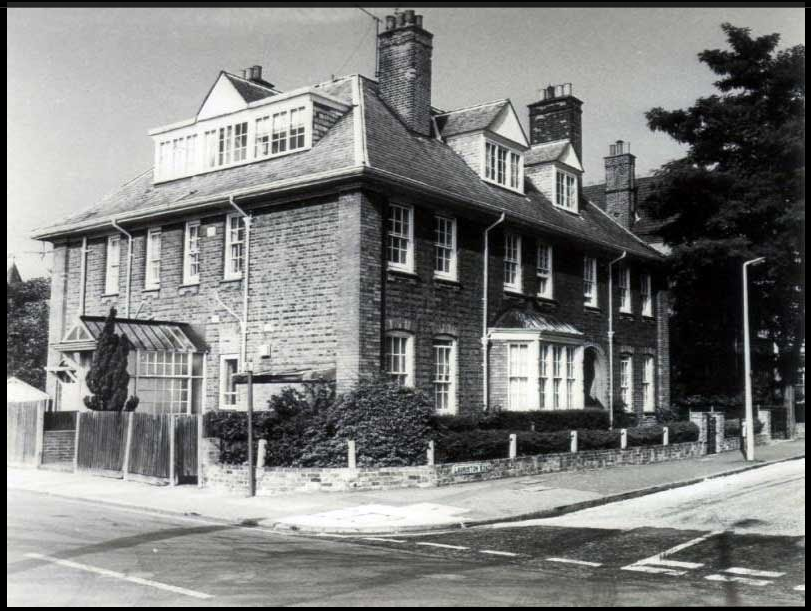

The family lived in Wimbledon, at Red Branch House, 1 Lauriston Road.

Red Branch House, 1 Lauriston Road Wimbledon. Built by Amy Graves in 1895.

Photograph courtesy of Fundacio Robert Graves www.fundaciorobertgraves.org/en/origins-and-childhood-1895-1909/

Rosaleen Graves was very close to her brother Robert during childhood. Writing to Robert in 1973, just before his descent into Alzheimer’s, she told him that, ‘all through my childhood and youth you were the person I loved best in the world.’ When at the age of four and a half, Robert was rushed to hospital with scarlet fever, she had hidden his most precious Christmas present, a toy soldier’s helmet, to keep it from being destroyed as potentially infectious.

1904: Robert, Charles, Amy, John, Clarissa, Rosaleen

Photograph courtesy of Fundacio Robert Graves www.fundaciorobertgraves.org/en/origins-and-childhood-1895-1909/

Life as a VAD Nurse

Rosaleen Graves had ambitions to be a concert pianist and was awarded a Diploma from the Royal College of Music, but when WWI broke out she;

joined the Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD) on 17th September 1915, aged 22. She served as a nurse at No. 54 General Hospital, Wimereux, France from 23rd November 1917, until 14th March 1919. This base hospital, known as “London General Hospital,” was in use from July 1917 to May 1919. Service records show that Rosaleen received the 1 Scarlet Efficiency Stripe on 15th October 1917. Awarded by a chief matron or commanding officer, stripes signified nursing efficiency and were worn on uniform dress sleeves. They were red or blue, depending on whether a nurse was under contract to the War Office, or the Order of St. John.

Founded in 1909, the Volunteer Aid Detachment was supported by the Red Cross and the Order of St. John. It consisted of untrained nurses who worked in military hospitals under the control of the War Office, or the Joint War Committee of the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John. Rosaleen served under the latter. VADs had no prior nursing training and were predominantly unpaid volunteers. Rosaleen and her fellow VAD nurses cared for sick and wounded soldiers both at home or abroad. They worked at various locations including Army hospitals and convalescent homes.

She later attended Merton College, Oxford, to study medicine which heralded her achievements in ‘Merton Combatants ‘ 1

In the book We Will Remember Them: Voices from the Aftermath of the Great War by Max Arthur, there are several different references to Rosaleen’s wartime experiences as a VAD nurse.

‘There was a terribly infectious pneumonia epidemic, that developed among the troops, so that I didn’t get back home until well into the spring of March or April 1919. We were nursing some desperately ill men – some of them had been all through the fighting at the Front and escaped death – then died like flies in this epidemic. Great big, beefy guardsmen were struck down, and it seemed as if the germs preferred them to the wizened little Cockneys, and they died like flies. Only after that was over was I able to come back. It seemed to me rather a useless life then, just teaching little girls to play the piano after what I had been through. The whole experience of the war had a lasting and dramatic effect on my life.’

‘We heard about the Armistice in our camp just outside Boulogne. I was on night duty, so I was allowed to take the morning off, providing I got some sleep in later, so I went into Boulogne. Oh, there was such excitement! There was a notice up on the door of the town hall which said ‘Onze heure du matin, la guerre est finie.’ Perfect strangers were hugging each other on the street and crying. Middle-aged men were hugging each other saying,‘vous etes content, mon ami?’ ‘Ah oui- je sius content!’ It was all very exciting.

There was immense relief all round, but especially among the British patients I’d been looking after, because all the ones who weren’t very sick dreaded going back into the line. I went into the mess room – and we were allowed to wear beautiful dresses there – and I sat down at the piano and I played the Chopin prelude called the ‘Eleven o’clock’, because it has got those great clanging eleven chords. It seemed to me a great way of celebrating the end of the war.’

The Graves family on November 22nd 1917 Standing: Rosaleen, Charles, Alfred, John. Sitting: Robert, Amy, Clarissa.

Photograph courtesy of Fundacio Robert Graves www.fundaciorobertgraves.org/en/war-1914-1918/

Rosaleen and Robert; Post WWI

Rosaleen and Robert Graves, c1920

Robert was not the only poet in the Graves family: Rosaleen also wrote poems during the war years and many of them were published. When WWI finished and Rosaleen returned to England she felt her life needed to be spent doing something useful. She is quoted in We Will Remember Them: Voices from the Aftermath of the Great War ;

I was up at Oxford, visiting one of my three brothers – my brothers all got up to Oxford on scholarships from Charter-house – and we were out on the river in a punt. Someone said to me, ‘What are you going to do now the war’s over?’ I said ‘I don’t know. I don’t want to go back to nursing, because I’d have to go back to scrubbing lockers and all my experience will be wasted.’ He said, ‘Why not try medicine?’ It hit me like a sledgehammer to the head – that was what I would do. I would have another career.

When I got back to England there was a mood of change. I was never politically minded, and it never concerned me – although I had no doubt it should have been granted before – but it was after the end of the war that women were eventually given the vote. The theory was that women had worked so well in the war, taking on men’s jobs and stepping into the breach, not just nursing, but in engineering and factories, that they had earned the vote. After the war there was quite a different feeling among women, and I did notice that.

Rosaleen continued to write and among her published works are “Night Sounds and other poems’, published by Basil Blackwell in Oxford in 1923, “Snapdragons Poems“ by Rosaleen Graves Cooper and “The Silver Mirror. Breton Folk Air’, words translated from the Breton by A.P. Graves and arranged by R. Graves (1928).2

After the war Rosaleen trained as a doctor taking a position at Charing Cross Hospital in 1926, and later became one of the first female G.P. s in the country. She married James Cooper in 1932, the couple had three children and Rosaleen continued to practise in London and Kent. A letter to her brother Robert written in 1939 gives us a small insight into her life, her love for her brother, her future and her relationship with her husband, and makes interesting reading.

‘Darling Robert

You’ll be wondering why I haven’t thanked you long ago for your ” Poems ” – which were (or was?) my nicest Xmas present – far & away. It’s fun finding ancient friends & unknown ones in the same volume.

Thank you very much indeed, my dear, for sending it to me.

The reason (as you may possibly have guessed) is that your prophecy about Jim’s making a kind of reconciliation came true – & in spite of what you say, I’m taking him seriously. Its not that he’s recanted or apologized or anything like that – such behaviour would be quite impossible for one of his type – but almost immediately after I’d told him of my visit to the lawyer & his verdict – he propounded a scheme of our working a joint practice in Devon & sharing a house again – so it looks as if the thought of losing family life had shaken him a bit.

He still writes to me coldly as “Dear Rosaleen…from Jim ” but is quite friendly on our rare meetings & is really making communal plans at last – which have some sort of financial sanity. I don’t know if we shall ever establish a really good personal relationship again – but I’m content with this at present – & even if I get no personal happiness out of a new start – the boys will – as they adore their father.

I’ve had a small present for you for months – ×××× [crossed out] a puzzle- picture of Napoleon & his wife & child masquerading as a plant of flax. Its in an old frame & I should think is a contemporary of those times as no-one now would bother about Napoleon’s family. It only cost 1/-1 in a shop where they re-make mattresses – & I thought it might amuse you – but I’ll have to wait till [until] I see you as it would probably break in transit.

My 2 German refugees have at last gone to Australia, poor things. Its absurd for an elderly business man to be sentimental about a Xmas tree, I know, but I felt very sad when they said “there will be no Xmas trees in Australia –” We were all frozen up at Xmas – car, pipes, & kitchen boiler but had a very good time all the same with a giant Xmas tree, & lots of parcels for the boys.

We go to Devon in about 3 weeks. I’ve sold my London practice (for only £325 after 10 years) to an old fellow-student at Ch X Hosp. [Charing Cross Hospital] The Kent practice is too small & too scattered & will just have to disintegrate. In Devon I’m to get £350 a year as assistant in the partnership – & when Jim has had a job at Ch X H [Charing Cross Hospital] & joins the practice (? in August) we’re to get £600 between us. The firm will pay all surgery expenses & a car allowance – & we’ll have only 1 lot of domestic overheads – and if it does well we could later buy a share in the partnership, so I’m very pleased about it.

The village, Bishopsteignton, is 2 miles from the sea – & overlooks country very like the Barmouth Estuary – with lovely rolling wooded hills & the river Teign – very broad. It will be lovely to get back to village life again, after this dreary suburb – Well – wish me luck! I think I shall get some at last.

I shall have to become Rosaleen Cooper, I fear, in such a conservative district & sink into married oblivion – so I’ll sign myself for the last time as your most loving sister

Rosaleen Graves’

Courtesy of St John’s College, Robert Graves Trust.

https://graves.uvic.ca/diary_1939-01-12_01_enc.html

Life in Bishopsteignton

On the 1939 register Rosaleen Copper is stated as living at Brendon, now no. 6 Newton Rd, later renamed Merrivale. She worked as the G.P from 1939 until 1964 covering the area of Bishopsteignton, Teignmouth, Shaldon, Chudleigh, Bovey Tracy and Kingsteignton. With the return of troops from Dunkirk at the end of WWII, Dr Cooper swung into action, taking care of them while they were billeted at Cockhaven Manor. Rosaleen and Jim’s marriage was dissolved in 1943. She continued to live in the village after she finished with her practice, and at that point lived at ‘Parknasilla‘, now no. 48 Newton Rd. and later moved to 53, Cockhaven Rd. during the 70s and 80s. Her sister Clarissa was at Parknasilla in 1966, and produced this watercolour, thought to be a view from that house of the house opposite on the Newton Rd, then known as Milestone.

Clarissa Graves’ Painting

Milestone. Bishopsteignton. S Devon, from the rear garden.

Rosaleen’s three sons Dan, Roger and Paul all went on to make news themselves.

In 1956 Paul, then an undergraduate at Oxford, was kept prisoner for four weeks by rebels in South Morroco, where he had gone for a holiday. Then in 1959, brothers Daniel and Paul were involved in a near lethal crash in Austria when their car was struck by a train on a level crossing near Kitzbuehl. Paul and another passenger received multiple injuries including broken legs and skulls, when the car was hit by the train and dragged for forty yards. Daniel and two others escaped from the car before the train struck. Paul had to be cut from the wreckage. The car, an old Volkswagen, was the same one that the other brother, Roger, had taken to Budapest after the 1956 Hungarian revolt, when he and his companions, one of whom was the granddaughter of Sir Stafford Cripps, were arrested and imprisoned for 16 days. On his return he was sent down from University for being absent without leave.3

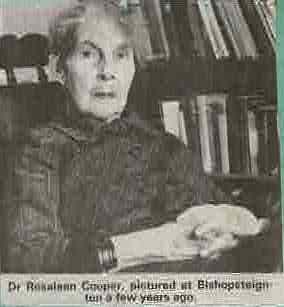

Dr Rosaleen Cooper photographed in Bishopsteignton

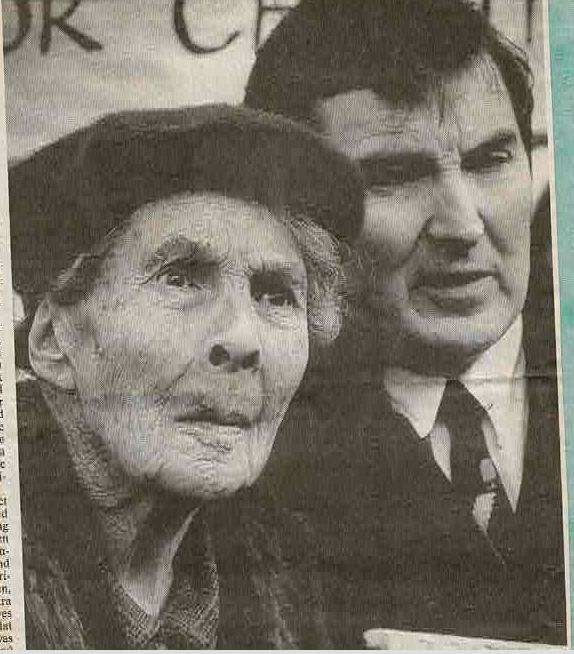

Later in life Roger, by then a businessman and journalist was imprisoned again in an Iranian jail on charges of spying. His mother campaigned tirelessly for his release, and after five years, and without being brought to trial, he was released and returned to England. Unfortunately Rosaleen had died whilst he was in Tehran. Roger’s nephew Simon had offered to take his place in prison so that Roger could attend her funeral, but that was denied.

Rosaleen Cooper outside the Iranian Embassy with her son Paul

Rosaleen was remembered locally as a quite eccentric lady, whose driving was renowned in the village. Her nephew recalls; “She was really a remarkable woman. At 90 she still drove straight out onto the main road in Bishopsteington, and the locals know to be careful with Dr Cooper’s car!”

According to a later resident of Brendon; “Apparently her habit was to back out onto the Newton Rd, hit the hedge across from the house, then turn right to Teignmouth, or left to Newton Abbot.”

She was once reported as; at Exeter Magistrates’ Court on Tuesday, Dr. Rosaleen Cooper, of Brendon, Bishopsteignton, was fined £2 for causing an obstruction by leaving motor car at Goldsmith-street, Exeter for 55 minutes.4

She continued to write and in 1982 she published Games from an Edwardian Childhood, a collection of songs and games no doubt prompted by her own childhood memories, which was illustrated by her then neighbour Brenda Gilpin.

Brenda Gilpin’s illustration for ‘We are the Romans’ from Games from an Edwardian Childhood by Rosaleen Cooper

Brenda Gilpin’s illustration for ‘Crocodile” from Games from an Edwardian Childhood, by Rosaleen Cooper

At some point in the 1980s Rosaleen Cooper moved back to Wimbledon and died there in a nursing home in August 1989.