Early Memories

I have been asked to record (for the record), things that have happened in my life. I have a mini recorder kindly presented to me. I shall try to use this from time to time but perhaps (to be safe) I will put things in writing as well.

Some people say they can remember things back to when they were 5. I can clearly remember more than that. I can remember Dennis, a younger brother, who was not normal and had a curvature of the spine. I remember him laughing, and appearing to be happy. Sadly he died at a very early age.

I can clearly remember when I was three years old. Then, children started going to state schools at that age. On the first day, my mother took me down to the school at the bottom of the hill. When I got back home at the end of the day I can remember telling how the teacher was Miss Hudson, and she was very pretty. After a day or two my mother told me I could go to school on my own. I must have shown discontent, as she said that I was not to look miserable but to smile going down to school. I always did exactly as I was told, and went to school with what could have been a sickly grin. At the school gate a little girl said to he mother “Mummy, look at that boy”. Her mother told her not to look, as “he can’t help it”.

Another early memory was when Mrs Carpenter started a junior Band of Hope, after her husband, owner of Huntly hotel, ran a Band of Hope to keep the workers from drinking too much cider which they could have at a half-penny a pint, before going home to do a bit of wife-bashing.

We would go to Huntly, and start the meeting by singing “My drink is water bright, water bright, from the crystal stream”. Mrs Carpenter asked me how old I was (four) and then asked if I could write my name in joined up letters. Starting school at three, we could do that. When I had written my name (in joined up letters) Mrs Carpenter said “Oh, you clever little boy; You’ve signed a thing called the pledge”. I decided, when I was 18, it didn’t count.

Looking back on my life, much of it has been like a sit comedy series. Often at the time it seemed serious, but in retrospect it can raise smiles.

Family Memories

Families tended to be larger in the early days of the 20th century, as did Victorian families. In my family we were five brothers and two sisters. The eldest was Doris, (Doris Thirza), then Douglas Patrick (Dougie), Lilian Mary, John Parker, George Henry, Philip Charles, and Dennis, who died in infancy. I was born on 8th April, 1920, George was born on lOth June, 1916. The others were pre-war.

On growing up, the eldest were so much so, it was like having several parents rather than brothers and sisters. I seemed to be fetching and carrying for all these elders, almost up to the time of World War 2.

During and after the war I felt I was doing my own thing, and then, as my elders became more so, in later years I found myself more or less fetching and carrying again.

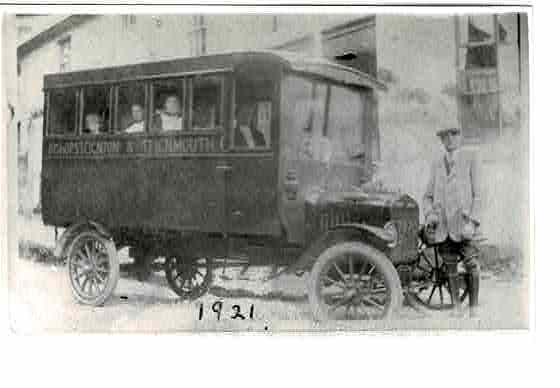

As each member of the family left school, they would be working in the family business. No such trade or profession like it exists now. My father ran a ‘bus service between Bishopsteignton and Teignmouth, and later also from Bishopsteignton to Newton Abbot. My first memory of his ‘buses was of ‘model T ‘ Fords.

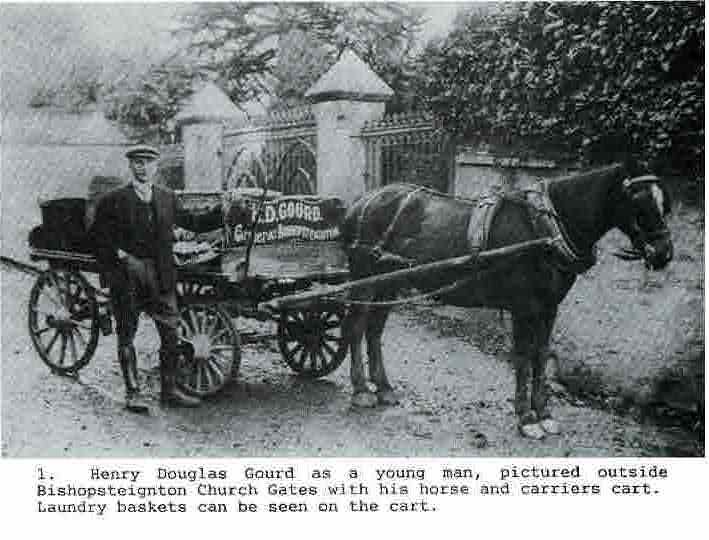

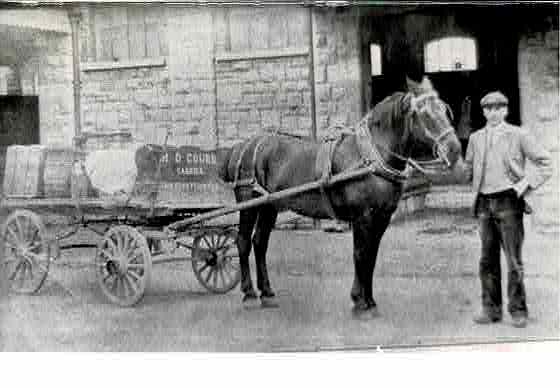

My father was born at Park Farm. His father went blind after having rheumatic fever, and never saw my father or younger son. Father left school at 12, and went to work at Huntly as “buttons”. He was ambitious and wanted to leave this lowly paid job for something better. In his early teenage years he left Huntly to be a self-employed carrier. He got himself a hand-barrow, and made journeys to and from Teignmouth, carrying anything for anybody.

In those days there were up to 8 millionaires living in Teignmouth, and he carried the large ‘mauns’, (baskets), of freshly laundered linen from the laundresses in the village to the big houses in Teignmouth, bringing back the soiled linen for laundering. The laundresses were mainly the wives of farm labourers, who were striving to makes ends meet, and perhaps even have one or two extra luxuries, like toothpaste.

One of the earliest orders he had was to bring a heavy chimney-piece from Devon Trading Co, the builders’ merchants, from Teignmouth to Huntly. He had help getting this weighty piece on his barrow, but when he got to Huntly , and staff there started to help him with this , Mr Carpenter, the owner of Huntly, stopped them, saying that he hadn’t paid THEM to carry it. My father struggled with this item as best he could, but it slipped and got a slight chip on it, whereupon Mr Carpenter, still annoyed with him for leaving Huntly to start on his own, made him pay for a replacement chimney. Such was the blow at the very start of his venture that he nearly gave up. He did however manage somehow to re-place the item, and went on to become one of the leading business-men in the area.

It was such hard experience that made my father over economical throughout his life. We all lived frugally. When other families and children had such toys as scooters, or peddling cars, my family had basic gifts at Christmas. To play games we even used to convert the cardboard boxes to make toys.

HD Gourd 1898

Gourd transport 1898

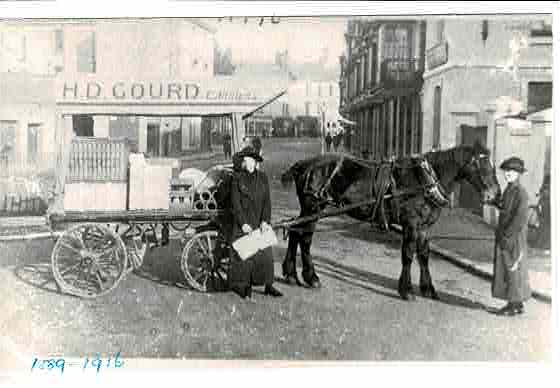

Such was the industry of my parents that in the early days of the 1900s (my father started as a boy in 1889 on his own) it was possible to buy what is now No 10 Radway Street, which had a stabling space adjoining, and No 12 next door, where his parents (my grandparents) could live. In those early 20th century days the transport was horse and cart. Later the cart was converted to a horse-bus, as people were asking if they could ride by sitting on the ‘mauns’. They could, at a charge of 4 pence. This charge was to endure right up to 1951, when the ‘bus service was sold.

My father, who I shall refer to from now on as HDG, took on as a secondary business, a coal delivery service, with his depot for fuel being at Coles Barn (now demolished). Deliveries were made by horse and cart, and the story goes how a Mr Apps (grandfather of Bert Apps who later worked for the firm) was working with the horse and he was asked to take coal to Lindridge, a grand house near the village, where it was urgently needed.

“Ban’t gwain to” was his reply “The hoss has had enough”.

The horseman’s word was law- and if a horse was declared too tired, that was it. HDG saw the need for a motor transport, and just before the first world war he bought the Daimler motor-car from Captain Templar of Lindridge. This had been the first horse-less carriage in the parish. The ‘body’ of the horse-drawn vehicle was mounted on the chassis of the Daimler, and so the first motor-bus of the firm was born.

Gourd 1906 Daimler

Came the great war (1914-1918) and HDG was called up for military service ,joining the RASC (Royal Army Service Corps). My mother, with Mrs Caroline Apps, continued to operate the carrying service between Bishopsteignton and Teignmouth, with the horse and cart still existing. The horse was called Violet, and worked throughout the war.

Gourd transport WWI

With the war ending, HDG returned with the motor-bus, and fairly soon after bought a model T Ford. With brother Dougie , soon after the war, becoming old enough to drive, a second ‘bus was in operation. Then a model T Ford ‘landeaulette’ car was bought, for car hire and taxi service, and sister Doris drove this.

Gourd bus 1921

HDG managed to purchase Nos 1, 3, and 5 Radway Hill, three red brick houses. He let these at a very cheap rent to a sister, Frances, (Harris) and her husband, nephew Sid Burgess and his wife Ivy, and a brother Fred Gourd and his family. Fred was bad a paying the rent, and Dougie was with HDG when Fred was asked for rent, and he urged HDG to be firmer about this. A day or so later when Dougie was passing No 5 Fred called him in, saying he had some rent for him. As soon as Dougie entered he attacked him, and Fred and his family were told to leave. Fred went off with a woman called Dolly, leaving his wife Annie to bring up a family of four brothers and two sisters, while she worked as cook at Huntly.

HDG never had a sense of security, even though his business was flourishing. Luxuries were frowned on, and holidays were non-existent. In addition to carrying passengers, people would hand a piece of paper to whoever was driving the ‘bus, with an order to get perhaps some fish, or a quarter pound of ham , and this would be bought during the quarter of an hour the bus was stopped at Teignmouth. Sometimes the people would wait for the bus to return, and collect the shopping, and pay tuppence extra for the service. If nobody met the bus, one of us had to deliver the parcel, and collect the money (perhaps one shilling and fourpence for the ham, and tuppence for the cartage.)

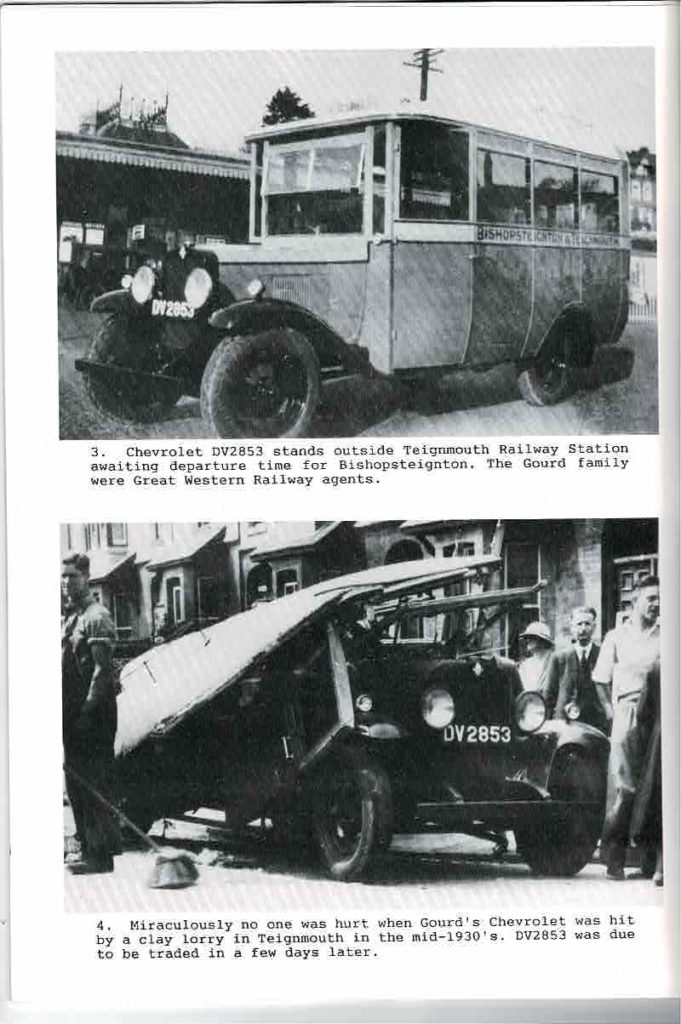

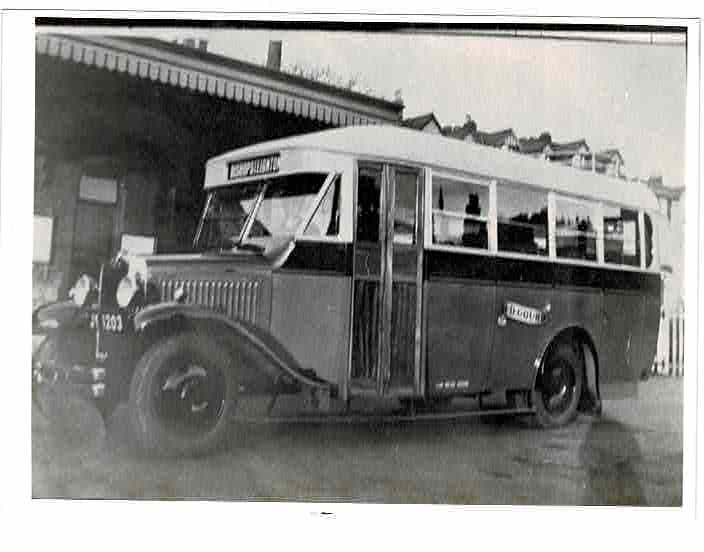

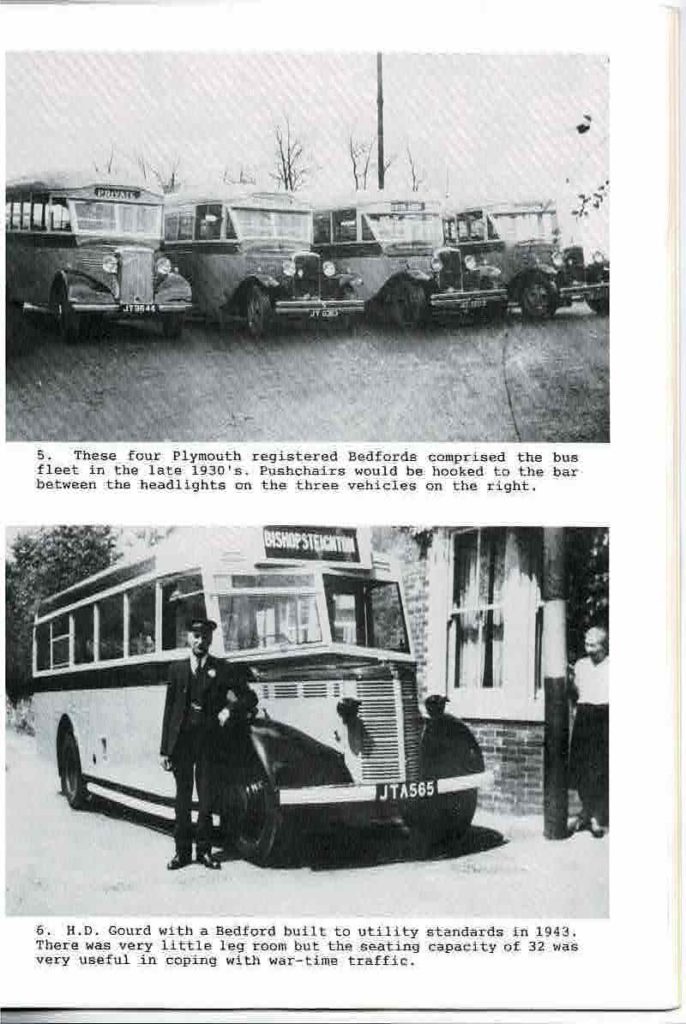

In the fairly early 1920s, Chevrolet ‘buses were with the firm. The chassis came over from Canada (left hand drive) and the body would be mounted at a coach-works at Teignmouth. These were 14 seaters. In the early 1930s Bedfords were used. Bodywork was by Mumfords of Plymouth. These were 20 seaters.

Deliveries of parcels was made with the aid of home-made pushcarts, which we called trollies. These were made with a wooden box mounted on pram wheels.

There were so many parcels to be delivered that as soon as school was over there could be several journeys made all over the village, including the big houses like Huntly and Bishopsteignton House, or the Moors, where Major Rayner, the MP lived. People were only charged tuppence per parcel, or threepence if the parcel was big.

On Saturdays during autumn and winter, brother George and I would go to the Commercial Inn, (later the Bishop John de Grandisson) to pick up loaves of bread, Cheddar cheese, bottles of beer and bottles of lemonade. The journey was then made to where-ever the syndicate shoot of Lindridge took place, and the food was for the gunners, keepers, beaters and brushers, who went in an extended line ‘beating’ and ‘brushing’ to make the pheasants rise up in front of the guns.

Beaters and brushers were mainly made up by builders’ labourers and similar folk, who managed to get Saturdays off, and they would earn at least five shillings. They also had the free lunch and Sir Edward Benthall always turned a blind eye to any bulge in the pockets of those who managed to ‘scrounge’ the odd pheasant.

The beer bottles were for the men and the lemonade bottles for the boys. Bill Mole, landlord of the Commercial Inn, was there to cut the loaves and cheese and give out. George and I sometimes had bread and cheese and a pastie (pastie also part of the lunch) but Bill Mole was mean in not letting us have any lemonade bottles. The Cheddar cheese, however, was the most delicious we have ever tasted. Any unused bottles, bread, cheese and pasties were taken back to the Commercial Inn.

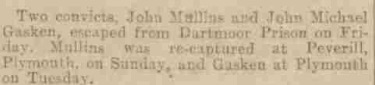

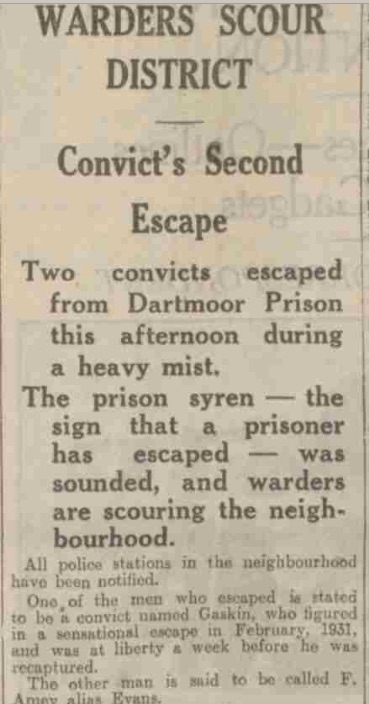

During these days there was an occasional escape from Dartmoor prison, which then attracted much publicity in the local papers. During 1928 (actually 1931) there was an escape by a Gaskins and Mullins. Gaskins was known as a nasty piece of work. They were both captured soon after escaping.

Report in North Devon Journal – Thursday 12 February 1931

Gaskins recapture Daily Herald – Monday 09 February 1931

During the autumn of 1928, (1932) there was another escape, this time by Gaskins and Amy (Amey). Local newspapers told of how they had been located at Newton Abbot and how a signal box near Newton Abbot station had been broken into and GWR issue trousers had been stolen.

After George and I had delivered the food to near Wood Lodge, we started on the return journey. Near Wolves Grove Farm a man came out from over the hedge. He was not a very large and we could see that he was wearing blue trousers with a thin red line down the seams. We had seen photos of him in the local papers. “Its Amy” said George. “Hello lads’ he said, “and where have you been?” I said we had taken the cheese and pasties to the beaters and brushers. “There” he said, “and I’ve left it too late. I’ve been beating up at the end of the field so I’ve just come.” With his steel rimmed glasses and soft voice, he seemed such a nice old man, we didn’t feel frightened despite our young years. (George was 12 and I was 8). He scoffed a pastie and bread and cheese and was full of pleasantries. I asked him if he would like a bottle of beer, “Oh yes please ” said he. George said no we couldn’t because they were counted. He didn’t protest at that and let us on our way.

Then George said we should not say anything or we would get into trouble. That night, when we had gone to bed, we heard someone at the front door. George looked down from the bedroom and recognised Inspector Taylor’s black police Humber by the front door. “They must have found out” said George, “We shall have to go to the reformatory.”

We then heard laughter – and Inspector Taylor saying, “Well, just tell them.” Our mother then came up to tell us that the second keeper, who was a big beefy man, had seen us giving Amy food, and had reported us. We always despised him after that. He had had a double barrel gun with him, and could easily have taken the old man. He could have been the hero of the day, instead of which even Inspector Taylor had a poor opinion of him, as did others.

The next evening it was announced on the radio that Amy had been captured near Cowley Bridge, Exeter, and we cried ourselves to sleep thinking of our poor old man back in prison. (Shades of “Great Expectations”).

2nd Escape Headline, Evening Telegraph Nov 16 1932

Evening Telegraph Nov 16 1932, 2nd Escape Article

Sunday was ‘bus cleaning day, summer and winter. The older members of the family cleaned the bodywork of the ‘buses with buckets of water, sponges and chamois leathers. The youngest of us cleaned the wheels with brush-heads (&buckets of water). In the winter the water was just above freezing point, and our hands and fingers would be blue with the cold. HDG said the colder the water, the better the polish (shine) was.

The Austin taxi was also used for weddings and funerals, and a glass-like polish was achieved by using a special wax polish called Simonize. It was also known as elbow-grease, because that is what it took to get the smear marks off. The result was a mirror-like car.

Gourd Chevrolets 1930s

In 1936 brother George persuaded HDG to get a second-hand Chevrolet van, so that the carrying side of the business could be expanded. This was a lorry on which hoops and a canvas cover could be placed. Such was the demand for this type of carrying services, whether for bringing bricks from the brick works at Kingsteignton to building sites, or moving furniture pieces, that HDG soon bought a new Bedford van (30 cwt). It was on this I learned to drive, from my 17th birthday in April 1937 onwards. Brother George taught me.

Gourd bus 1933

A cousin of the same age group drove for a local butcher, a small delivery van, and showed much more confidence than me, by driving at goodly speeds around the village. Driving tests had just come in, and he confidently went to Exeter for his test, and failed. The general talk was that “if he failed Phil Gourd doesn’t have a chance of passing.” On the appointed day, I reported to the testing station, and made sure I would not show signs of over-confidence, so I drove very slowly. At the end of the session the examiner said that I was painfully slow in driving, but as I did all the motions correctly he would issue a “Pass” certificate. My cousin excused his failing and my passing by saying that he had the notorious strict examiner, whilst I had the cushy one. A month later he went for his second test, this time having the same examiner as me – and failed. It seems he heard about my cautious driving and also drove slowly, perhaps too slowly.

The trade in removals and local carrying services became so popular that during the post-war years the van business exceeded the ‘bus and coach activities. With both the coach side, and the goods (especially antiques) vehicles did frequent journeys into Europe.

Gourd buses 1930s 1940s

The Outbreak of War

One of those moments always to be remembered was on Sunday, 3rd September, 1939. Hitler’s German army had entered Poland. The BBC, usually quite over-polite with announcements, had a newscaster make a statement that sounded like a military order. “Stand by for a talk by the Prime Minister at 11 o’clock”.

Mr Neville Chamberlain spoke softly, reminding of how he had tried over the years to keep the country at peace. Britain and France had a treaty of assistance with Poland, and Hitler had been given the notice that unless German troops were withdrawn from Poland by the morning of the 3rd, Britain and France would take appropriate action. Neville Chamberlain stated that no such committent had been received from Hitler, and therefore, we were at war with Germany. Neighbours had come in to listen to the announcement, and dear old Mrs Searle from next door wept as she said how funny it was going to be without the boys (meaning us). That radio announcement was the most momentous ever heard. All most dramatic.

The Crown Jewels

Being Sunday, my father was relaxing in his Windsor chair reading the newspaper. During the mid-afternoon, three city suited men came up the street in a super Humber Snipe. They asked if they could see father. They mentioned the exhibition of replica crown jewels that had been on show in the empty shop in the Triangle at Teignmouth, and asked if a van could be there to move packing cases that would be ready for transporting, to the basement of Bodmin old jail (now Town Hall). Brother George and I had seen the van arrive at the shop on the Thursday. We saw how the van staff carried cardboard cartons and tea chests, quite easily handled by one man. They were just papier mache replicas, with stones for jewels.

The exhibition was organised by the Daily Mirror,and each day, on the front page, would be a little square in which the information as to which town etc. the replica crown jewels would be on display. Thursday 31 Aug they arrived at Teignmouth, for showing on Friday/Sat 1/2 Sept.

When the three men spoke to my father, they did not mention replica crown jewels, but said they wanted the packing cases moved. They relied on my father’s honesty regarding the charges. The important thing was to get the job done. When we arrived on the Monday morning (4th Sept), we found not the cardboard cartons we had seen arrive, but heavy deal cases, only manageable by two men. Cyril Extence, antique dealer, who lived around the corner, came and asked my father what was going on, as there had been vehicles toing and froing up to past midnight, with banging going on. The three men in city suits were watching the loading, and outside Smith’s the stationers was a police-car. A police motor bike was also nearby.

What had happened was – this was a switch. We found later that a van from the ministry of works had brought the real crown jewels to Teignmouth, and had off-loaded them, under police supervision, and had then boxed the replica crown jewels to take back to the Tower of London. There was not time for the Ministry van to go on to Bodmin, and then back to London in time for the (replica) crown jewels to be on public display by 10 o’clock on the Monday morning. The three city-suited men gave a sigh of relief when we had trundled the crate down along the flag-stoned corridor into the old cells with bars. A strong hint was given to my father what was really in the crates. When we got back, he had us around him in a half circle and said this was a matter of great security and therefore secrecy. We were not to say anything, to anybody, for at least 50 years.

Anyone knowing my father and what a strict disciplinarian he was, may understand why it was in fact half a century before this story was told. It was then published in various newspapers. The Queen’s lady-in- waiting was given a copy for handing over to the Queen. Information about the crown jewels indicates they were transported to a couple of caves in central Wales, where the temperature and humidity was ideal.

It so happened that I was in army uniform the next time I saw the replica crown jewels. These were behind thick glass and looked like the real thing. The Yeoman of the Guard (Beefeater) who was giving the commentary to a guided group (mostly Americans) said how “We are not afraid of Hitler’s bombs – and to prove it here are the crown jewels for all to see”. He was a Coldstreamer, and I do think he thought he was with the real Crown Jewels.

HIDING THE CROWN JEWELS – (Now it can be told)

by 2661132 Phi1ip Gourd

During the autumn of 1939, the Daily Mirror (then rather more Royalist in outlook), sponsored a touring exhibition of replica Crown Jewels, giving daily information of where the display was. There was great interest in Teignmouth at the end of August when the Mirror advised that the showing would be at the premises of an empty shop in the centre of town.

My brother and I remember seeing the arrival of the van at the venue, when cartons and tea chests were easily carried by one man. The contents would have been light as the replicas were made of papier-mache and coloured stones. On visiting the show, it was difficult to imagine they were not the real thing. The show was due to end on 3rd September, the day war broke out. After my family had listened to that most momentous announcement by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, that we were at war with Germany, a black Humber Super Snipe drew up at our door. The three gents in city suits who emerged from the car had come to ask my father, whose trade was transport, if he could supply a van earl y on the Monday morning (4th September) to convey cases from the shop where the replicas had been on show, and convey them to Bodmin Jail house in Cornwall. At this stage, they said they would not go into details for price as the job had to be done and they would rely on my father ‘s honesty.

Arriving on that Monday morning, the 4th September, we found the cases were not the ones seen to arrive just a few days earlier. The consignment we handled was of heavy deal crates. During the loading an antique dealer who lived just around the corner asked my father what the devil had been going on through the night, with vehicles ‘toing and froing’ and banging taking place. By this time it became obvious there had been a ‘switch’. Our journey from Teignmouth to Bodmin was well escorted all the way with police motor cycles and cars always in view.

On arrival at Bodmin Court House cum Jail house, the three city suited gents were there with their Humber Super Snipe. With the aid of a trolley, the heavy cases were trundled down the sloping flagstones to their resting place behind thick bars. The three gents gave a visible sigh of relief, and one, during the excitement of the moment nearly let something slip out when my father commented that the cases seemed unduly heavy with the contents being just papier mache. Back at the depot my father got those who had effected this cartage, and threatened dire action if any word was breathed of this journey, as this was obviously a matter of national security.

Fairly soon after, when I was a guardsman and visiting the Tower of London, there, behind the thick glass were the ‘jewels’. The Yeoman of the Guard (a Coldstreamer) who was showing visitors around, proudly announced how “Little old Hitler can’t stop the Crown Jewels being on show”. Those replicas were pretty damn good….

The Crown Jewels – Epilogue

In fairly recent times, the retiring Constable of the Tower of London was quoted in newspaper articles as asking for information as to the whereabouts of the Crown Jewels during the war, so per se the great secrecy was somewhat relaxed.

Hearing accounts from various sources, it seems the Ministry of Works vehicle brought the real Crown Jewels to Teignmouth but did not have time to go on to Bodmin and back. The road journey then from Teignmouth to London was about 8 hours, which just gave time for the replicas to be displayed to the public by opening time at the Tower.

It is said that the Crown Jewels were, at some time, taken from Bodmin to a cave or caves in Wales.

Early Military Service Memories

The war was to change all our lives radically. Newspapers advised us of what we might expect, including rationing, voluntary services, when folk were asked to put their names forward to take on such duties as night wardens to make sure no lights were showing at night. Retired army officers were on duty at the school-rooms (adjoining) to fit people with gas-masks.

Cars had to be fitted with light-masks on the headlamps. This was like a sideways top hat, with slits, so that drivers could just see at night, with the minimum of beam showing. Brother George volunteered for the army, and went into the RASC, just as his father had done during the first world war.

My 20th birthday was on the 8th April 1940. It was felt that if I volunteered before being called up, I would have more choice of what unit I went into. I was advised that if I quoted Kings Rules and Regulations, giving the reference number, I could be in the same unit as an older brother. I had a date to report to the recruitment office in Castle Street, Exeter, and brother John gave me a lift in his lorry (he was driving a Harrell lorry to Exeter). He told me that when going for a physical examination I had to take clothing off, and in the cold I would feel the need to relieve myself in the toilet, so on the way into the recruitment centre I made my duty call, only to be asked, immediately on arrival, to present a sample in the little bottle I was handed. I had to admit to the M.O. that I could not ‘go’ , and he tried to help by whistling, which he said sometimes did the trick. Sadly I was ‘dry’, so it took some time after drinking glasses of water that I could eventually oblige.

I told the sergeant about my application with Kings Rules and Regulations, but he was not keen on listening. He said a fellow like me, tall and fit, should be better in the Guards – “Fine boys in the Guards” , he said, and after a lot of procrastination, signatures were made and I was assigned to the Coldstream Guards. This was something in the long term I did not regret. I was to have more interesting experiences, meet more world famous people, than ever could have been dreamed of. I was told later that the (Coldstream) recruiting sergeant received a bonus for every Coldstream Guard he enrolled. (What some people will do for a shilling!)

The next 7 years were the most influential in my life. This period can be classed as “concentrated experience”, when sanity was preserved with humour. A rail warrant was issued to me, with instructions to report to Caterham barracks, Surrey. This was my first journey to London and district. The route was by Central Line (Southern Railway) from Exeter to Waterloo. There was time for a break for a half pint at the Nelson Inn by Waterloo station. Being young and green, I thought all ladies that wore fur coats were society ladies, as written by William Hickey in the Daily Express. One such ‘society’ person came into the bar – who I thought must be one of William Hickey’s society dames, until she spoke in a cockney accent – “Evenin’ Bert, cor ’tis pissin’ dahn ahtside”. Obviously NOT one of William Hickey’s society ladies.

Caterham is on two heights, there is Caterham proper and Caterham-on-the-Hill. The barracks are at the top of the hill, quite a walk from the station. There was a sergeant barking staccato instructions at new recruits as they arrived. Each recruit is ordered to follow the orderly, who marched in very quick time to the dormitory across the square. There would be about a dozen or so, all new recruits, having instructions shouted at them. The general arrangements were to be made the following morning, and we were each allocated a bed for the night and, after stilted conversation, all trying to hide their nervousness, we all tried to sleep, with the barrack clock in its central tower striking the quarter hour.

The first call the next day was to the quartermaster- sergeant who barked out a number to each of us, “Remember it IF you can!” My number was 2661132, and like all the others, this was to be written across my heart for the rest of my life. Then came the issue of boots with the instructions “Remember what size IF you can!”. The vests were woollen and the shirts were prickly to say the least. I had never been used to wearing wool next to the skin, and wearing was sheer torture. Those from the north were used to wearing wool, so they were not affected. It took quite a time to get accustomed to this harsh wear, during which time I hated life.

On the second day we were billeted in the barrack room in one of the three-floored blocks, all named after generals. My block was Monck block after General Monck who was the founder of the Coldstream Guards. Each squad of about 30 were under an NCO. We had Lance Corporal Bouncer, a Plymouth man. Sleeping at the end of the barrack room would be a Trained Soldier. Trained Soldier was a rank (although still officially a Guardsman). We were not yet Guardsmen and would not be until we had passed the drill tests. Our rank was Recruit. Address was L/Cpl Bouncer Squad, Monck Block, Caterham Barracks.

The Trained Soldier had much the same influence and power over us as a sergeant normally would, and the Lance Corporal had much the same power as a Sergeant Major would. After practising drills we had lectures and after the tea break we were confined to the barrack room, for Shining Parade, when we spent all of each evening polishing our boots (which were dull when new, but which had to be shining like glass in a short time), blancoing and brass polishing. No talking was allowed during shining parade and no smoking, except any who had a pipe. The barrack room floor had to be ‘bumped’, that is manual shining, mirror like. No-one could walk in the middle of the barrack room, only behind beds to get from one to the other. This programme was to endure for several weeks until we had passed drill tests and then we were only allowed to go as far as Purley, (nearby south of Croyden).

Caterham was the depot for all the five regiments of foot guards – Coldstream, Grenadiers, Scots, Irish and Welsh. The NCOs, warrant officers and officers were from all the guards’ regiments. The Commandant was the Earl of Romney, a Coldstreamer. We did not see much of the officers during our first weeks at Caterham. We saw them at passing out parades, when they passed or failed squads.

The Commandant was a gentle giant, and after some weeks, he passed us, sufficiently to be allowed out of barracks, to go as far as Purley. Our rank was still recruit and we would not become guardsmen until the final passing out parade, after which we were. Getting out of barracks was tough, as It meant passing the scrutiny of the sergeant on gate duty. Often someone was sent back to improve on their turnout. With a pal, I decided to chance it, and go to London on the tram that ran from Purley. There was a Grenadier sergeant on duty outside the Greyhound Inn at Croydon, to make sure no recruit was on the tram. We ducked down tying, untying and re-tying our bootlaces while the tram stopped at the Greyhound. I seemed an interminable time, and other passengers upstairs must have been puzzled at two soldiers tying and untying their boots.

At last we were on our way. The route up to London passed over Blackfriars bridge, along the Embankment and back over Westminster Bridge. We parted company because my pal had a friend (family) to visit, and whilst I was going along Piccadilly, there was an air raid, with lots of noise, so I went into the Princes Bar. At the far end, was a gentleman in a smart tweed suit, “Ah, guardsman, have a drink,” said he. “Give the guardsman a whisky.” he told the barman. I thought it safe enough to tell him I was up from Caterham, “How interesting” he exclaimed, “I’m the Adjutant.” He made no other comment about being out of bounds.

On returning to Caterham, I learned that the adjutant was Captain the Lord Brownlow, an absolute tyrant. It was with trepidation that I went on parade for Adjutant’s inspection, for passing out. Came the day, and before the Adjutant got to me he noticed the guardsman on the front row holding his rifle at the slope, had an”unclean” fingernail. ”Take them away, they’re filthy” was his order. So the whole squad was failed through one recruit having a dirty fingernail.

Brownlow had a limp, which made him walk with an up/down fashion and he was always referred to as noticing “Boots. Capstar. Boots. Capstar” as he walked along the ranks. When he got to me, he stared long and hard – I thought I was “for it”, but perhaps he was not so sure, and eventually walked on.

Lord Brownlow was already famous as being one of the escorts of Mrs Simpson on the dash in the Buick car across France, when King Edward VIII was abdicating. The other escort was Captain Waddilove (Coldstream Guards) who was also at Caterham then. Brownlow lived in what has been described as the best Queen Anne house in England. He was extremely difficult, even to the extent of quarrelling with his son and excluding him from his will.

THE WAR WILL SOON BE OVER •••••••

A great source of information seemed to be from the conductors on the Hants-Dorset ‘bus that ran through the camp at Pirbright. The route was from Aldershot, through Pirbright, Brookwood and Woking etc. From their portable radios, they picked up the news as they went along. “The war will soon be over” was the shout from the ‘bus one day, when Germany invaded Russia, thus breaking the peace treaty current up to then. “Hitler’s made a mistake , we know how strong Russia is and he doesn’t seem to know it”.

The war was to go on for years yet.

“The war will soon be over” we were told again by an exited conductor. “Hess, the Deputy Fuhrer, has landed in Scotland from an aeroplane. This is to sort out a peace treaty”. This was certainly one of the sensations of the war, and all awaited developments. Hitler declared Rudolf Hess insane. Dr Goebbels put out other various bits of propaganda. At that time, those of us who were to be personally involved with Hess had no idea of the interesting days ahead. We had heard that Hess was being held in the Tower of London, guarded by the Scots Guards. A section of us were called to the parade ground, for special duty. The adjutant told us that we were to guard a V.I.P. (very important prisoner), whose name he could not then divulge. We were to be sworn to secrecy if and when we recognised the V.I.P.

We were bundled into a small canvas covered truck, which was then sealed closed, and went on our way. After a fairly short journey, we felt the vehicle ascend a short way, and then stop. When the canvas was untied we were by a villa with a small turret tower. We went inside, and up a spiral staircase to the first floor landing. A (double) door opened, and there was a corporal, with a guardsman standing on either side of a grey suited man with bushy eyebrows and glaring eyes. It was Hess (easily recognisable).

I was in the middle of the trio facing them, so our eyes met. Hess pointed to me and shouted “Shysenhausen”. I felt my jaw drop at what was such an insult, and my instinct was to respond in a similar way, but the corporal escorting him said “He wants to go to the toilet”. So, our first duty with Hess, was to escort him to the loo. He was an awkward customer, deliberately bumping into both of us on either side of him as we walked. My thoughts were that he would be making an escape attempt – if not then, some time. My thoughts were right.

Our sentry duties were two hours on, four hours off. When we got back to the Training Depot (Pirbright) the smiling adjutant told us we had done a good job, under difficult circumstances and we could have the rest of the day off. We decided to go to Aldershot Hippodrome to see Arthur English, who was a leading comedian then. When we were on the ‘bus, we passed through the pine woods, and along the way could be seen the turret of the villa where we had spent the night. As we were still sworn to secrecy we instinctively turned our heads to look out of the opposite window, when the ‘bus conductor said to the whole load of passengers ”You see that villa up there, little Ole Hess is in there” So much for security.

It was November 1941 when we heard the now almost familiar call from a ‘bus conductor. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbour and America was to come into the war with Great Britain, who had stood alone until then – with, of course, the great help from our colonies and empire.

Philip Gourd 1941

The war was to go on for years yet….

There was what was called a ‘duty’ battalion at Wellington Barracks, from whence public duties were made, such as guarding Buckingham Palace and St. James’ Palace as well as the Bank of England. At the bank patrols went along the corridors where bullion was kept. At the end of each guard, each guardsman was entitled to receive one shilling, direct from the mint. These could be sold in the city for much more, being brand new. One sergeant used to use the top of the ‘tortoise’ stove to warm any old shillings, keeping all the new ones for himself. So instead of the shilling being ‘warm from the mint’ they were warm from the stove. When the sergeant was complained to that the shillings were old ones, his reply was always, “Well they’re warm ain’t they?”

A pleasant station was at Albany barracks, in Albany Rd., known as Regents Park barracks. The main fly in the ointment there was the Regimental Sergeant Major, Tibby Brittain, probably the most famous RSM ever. To say he was a martinet was to put it mildly. However if anyone was working closely to him he had his human and amusing side.

At Regents Park I was put with the transport section for some time, and I had an open Austin 10 painted in army grey, but still a nice little car to drive around. One duty was to drive Tibby Brittain down to view the guard on duty at Buckingham Palace and St. James. The car would physically tilt to the left when he sat in it. I was as slight as he was heavy. The official route was to enter the Mall by Admiralty Arch and, or course, the guardsmen could see the car coming, so were acting their best.

Tibby liked to be driven down Bond St., where his left arm, with its enormous royal coat of arms signifying his great rank, would be in full view of the fashionable ladies and others along the street. One day he said, “Today we shall go down Constitution Hill and give them a surprise. We shall catch them unawares.” “You will surprise them sir.” I said, “We will surprise them man!” came his reply.

Approaching the left extreme guard, we could see the guardsman leaning slightly to get a better view of the Mall, in order to see us coming and, surprise, surprise, with no one else around he was either picking or scratching his nose. The bawl that went up from Tibby must have been heard in the Palace if the King was there. With the guardsman being stationed at Wellington Barracks at the time, I never knew what happened to him.

For a short time I spent duty with the fourth battalion, which was stationed (billeted) in various houses in and around Elstree. With the film studios being at nearby Boreham Wood, film stars and celebrities lived in the area, including Richard Tauber, the world famous tenor. I was in a house called the Leas, which had the luxury of running hot and cold water. To have the benefit of this meant getting to the wash-basins early, or the hot water was expended.

What was said to be the oldest house in England was in Elstree, owned by the Carlisle cousins, two popular singers in the theatre circuits. One night there was a terrific explosion, certainly more than the conventional bomb. A land mine ( large tube on a parachute) had hit the old Carlisle house, which of course was no more. The housekeeper was there at the time and was killed. Several articles of clothes, including shoes, were dangling on nearby trees. When the Carlisle cousins returned, their language was an education (in mixed company too!)

A concert party was arranged, and some of the local stars, including Richard Tauber, agreed to take part. The compère was a disaster, as this lance- corporal ‘smartie’ tried to be funny when announcing the famous stars. ‘You’ve all heard of Oct Tauber, well, here’s his younger brother Richard’ (Richard didn’t laugh).

I developed a severe cough, so much so that with all the hacking I eventually coughed up some blood. It seemed this was just from my wind-pipe, with so much coughing, and not from the lungs. The M.O. diagnosed me as having bronchitis, and I was ambulanced to Henley military hospital, where I spent my 21st birthday.

As we recovered, we were allowed to walk out, and out ‘uniform’ was a very ill-fitting and unflattering grey trousers and blue jacket. We were invited to various local functions by the locals, including whist drives and concerts etc. On recuperating I went back to Pirbright, where I was given very light duties. At Pirbright there was the A.L.E.C.Hut (Army Leisure Interest Centre) where in our own time we could attend tuition in languages, sketching, painting etc. Our sergeant Major, preparing himself for when we would be in Europe, attended the French language lessons. (He ended up in Italy.)

I took the painting lessons, and had Captain Langdon, RA as tutor. Quite a time after, these lessons came in handy, for sketching duty in the city of London. At that time there was no colour photography in England, (there still was in America of course). A record was required of bomb damage in the city immediately after raids, and six of us were assigned to make pastel (colour) sketches. One of my earlier ones was of St. Pauls. In the time allocated I managed to do two, so quietly kept one to bring home. It is still hanging in the passageway at home.

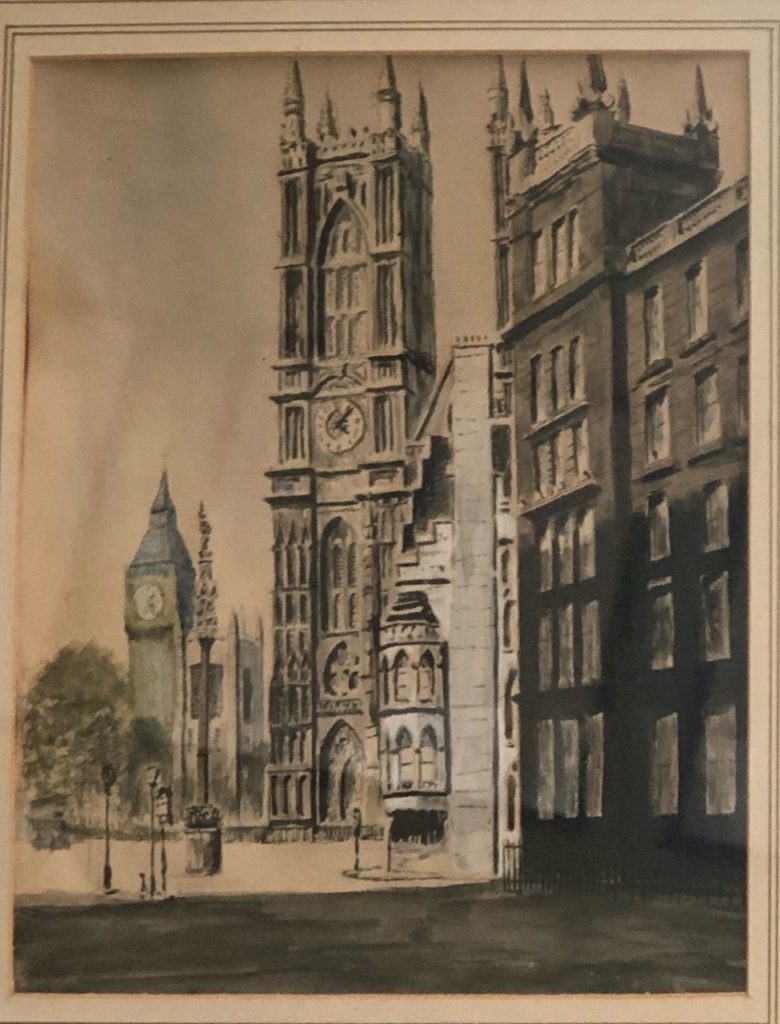

In November 1942 there was no annual Royal Academy exhibition at Burlington House, but instead a Forces Exhibition. I submitted some, most of which were accepted. One was of Exeter cathedral from the dean’s archway (oils)- another was of Westminster Abbey and Big Ben from the bottom of Victoria Street, and those are still among the pictures at home. The sketches were made when I was for a time at Wellington Barracks.

Looking towards parliament square from bottom of Victoria st. (Force’s exhibition Burlington House 1942). Phil Gourd

T.W.E. Girls

It was also interesting to take messages from RHQ to such places as the Foreign Office. The staff there seemed quaint, (eccentric). One day I had to take an envelope down to the basement, and passed a door with the letters T.W.E. When the door was opened there were three or four giggling girls at typewriters, known as the T.W.E. girls. I found that T.W.E. stood for ”Trading with the Enemy”. All this came about when a German soldier, stationed on Jersey, made friends with the manager of Boots the chemist there. He introduced himself as an employee of I.G.Farben, the medical manufacturers. When he was due to go on leave the Boots manager asked him, if he gave him the right currency, could he obtain some drugs which by now were unobtainable on Jersey. When the soldier called on his employers they willingly obliged, and also had an idea. There were certain drugs produced by such firms as Glaxo and Beecham in England, who could supply Germany, on an exchange basis, as the drugs required could not be produced in Germany. The management of I.G. Farben contacted embassies in Switzerland and Sweden, and the result was an exchange of drugs, made by either country that could not be produced in the other.

The result in London was the T.W.E girls, who were multi-lingual and exchanged drugs via Sweden and Switzerland, the arrangements being the successful two-way traffic.

The “T.W.E.” girls- (trading with the enemy)

Before being with the intelligence section, ipso facto, I was delivering messages from (Wellington) barracks to the War Office and Foreign Office. The War Office personnel were strictly regimental in manner, whereas the Foreign Office seemed to be staffed by rather quaint and vague gentlemen.

I was directed to the basement of the F.0., and entered the wrong door. Inside were some rather giggly girls with typewriters, and on coming out of that room, I noticed that the sign on the door read “T.W.E.” I was told this meant “trading with the enemy”.

My informant told me the so-say giggly girls were in fact clever linguists, typing letters in whatever language was necessary for what was in effect an import/export organisation.

From the same source I learned that this started with the German occupation of the Channel Isles, when a German corporal there, who had worked with I.G. Farben, called for a chat with the manager of Boots the chemist there. When he said he would be going on leave to Germany, to the place where I.G. Farben was, the Boots manager asked him, if he let him have the currency, could he bring back some certain drugs that were desperately short on the island. This the corporal did, and when he called at the I.G. Farben office, the management there were most interested, and the idea came to them that “the other side would be short of drugs only produced in Germany”. So they knew how such British firms as Beecham and Glaxo produced drugs not available in Germany, perhaps some sort of legalised “swap” could be arranged. This eventually led to an arrangement, through diplomatic channels, of trading via Sweden and Switzerland. The office with the giggly girls was a result of all this.

Pigs and Promotion

At Wellington barracks at this time was Major Carew, and in conversation he was interested to know I came from Devon, because he had associations with Haccombe House (between Combe-in-Teignhead and Newton Abbot).

He thought I could be groomed for some administrative duty, such as the Intelligence Section. He warned it would not be an easy number, as out of the line it would mean maps production and the like, but in the line there would be intelligence patrols and advance patrolling. He also said that for telephonic duty I would need some elocution, and with a few others, we would be tutored by Professor Felding, of Gower Street (by London University), who was a friend of his.

Professor Felding was a formidable character, with enormous teeth, which he showed when roused. He was perhaps more strict than a sergeant major; ”You must open your vowels ” said he when he opened his mouth widely, “and if you have not been practising, I will know”.

We were at a loser at both ends, because if we did not show progress we would incur the professor’s wrath, and when we went up to the barrack room dormitory “Talking like that” – we had everything thrown at us. I like to think these elocution lessons have held me in good stead throughout the years. Perhaps I am not as pronounced as I was, but still enough to make myself understood on the telephone.

The sixth battalion was formed at Harrow, and companies were billeted in various houses in the area. I went to headquarter company, in the M.T. (motor transport) section. Being in this meant an interesting and more varied life, with various journeys into London. Then, London was a joy to drive in. Traffic in wartime was light, as petrol was severely rationed. Buses ran more or less as usual, but there were fewer cars, and other than at traffic lights there was no stopping. Looking at traffic to-day, we never had it so good.

One profitable job was to collect pig-swill around the companies and take this to a pig-breeder near Northolt. He was a typical fat cat prosperous type, who tipped well, presumably in order to be kept on the list. It was surprising how much waste there was, with an enormous amount of uneaten food going into the pig-swill bins. Needless to say, taking pig-swill to this pig breeder was a sought after job, and the sergeant tried to be fair by “spreading out” this duty.

Our Sergeant Major was nicknamed “swill” Kirby (mainly because of his eating habits). One day 1 went to pick up my work-sheet from the M.T. office and was told “you’re taking swill around the companies”. This I took to mean driving Sgt/Major Kirby around, as I had just done a pig-swill job so did not think it was my turn yet. I knocked on “swill” Kirby’s door, and found he was not yet out of bed. I told him i was driving him around companies, which surprised him. “Let’s have a look at your work-sheet”, said he. I glanced at the order and to my horror saw it was for taking pig-swill. I hastily told him i had made a mistake and disappeared before he could chase after me in his undressed condition. It was another good day, with an exceptionally good tip from Mr. fat-cat.

The winter of 1941/42 was quite a cold one and one day I found my truck (a Bedford) was overheating. It was also making funny noises. I took it to the fitter, an RASC chap who was attached to the company, and he reported that the vehicle had a cracked cylinder block. This resulted in a court of inquiry, with the officer presiding being “Cush” Crawford, of shortcake biscuit fame. In giving evidence, I said how I had put water in the radiator, which shocked Captain Crawford. “Is it not a serious offence to actually put water into the engine? Whatever made you do such a thing?” He had never heard that radiators needed to be topped up with water to keep the engine cool. His chauffeur had always done what was necessary with his Rolls Royce, so he was not to know. When this was explained to him, he adjourned the inquiry session, so he could study things. Remarkable that someone with no knowledge whatever could preside over a court of inquiry into the reason for the cylinder crack.

The Coldstream guardsman, working under the RASC sergeant in the workshop, discovered on examination (proper examination, that is) that the defect was merely a cylinder head gasket. A fairly common occurrence. The RASC sergeant ordered him to take a hammer and chisel and proceed to try and crack the cylinder block, in order to make his evidence right. To his credit, the guardsman refused. Surprising how “comrades” can drop each other in the murk to save their own face.

The RASC sergeant did not thereafter have much respect.

Next is the story of the train that was machine-gunned by a Messerschmitt. There is a story behind the events leading to this.

Plymouth had been heavily bombed, and the king and queen visited the city the day after, which resulted in this being a great morale booster. During the evening, the royal train pulled into the tunnel nearest Teignmouth, between Teignmouth and Dawlish, as a security measure. During that night there was another heavy air-raid on Plymouth, and the king was asking whether the train should proceed to London or whether another visit to Plymouth was advisable.

Now we come to the question, who could have advised the enemy so quickly as to the whereabouts of the royal train? Someone did, and the enemy evidently knew where the train was, because the train from Newton Abbot towards Exeter and Paddington was machine-gunned when it emerged from the tunnel.

The king himself said that only a few in authority could have known of the whereabouts of the train, such as chiefs of police, chiefs of administration. He thought that after the war, when honours would be given, he could be pinning a medal on the chest of a traitor. (Not even other railway workers were aware that the royal train was in the tunnel, and other train drivers thought it was a troop carrying train there).

There is a happier aftermath. Ralph Howard also living at Bishopsteignton, was later to be the driver of the royal train, for the king’s last visit to Plymouth (post war), and had a certificate presented to him for this.

Patrol to Monte Sole, October 1944.

During early October, the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards were near Monzuno. We had no knowledge then of the massacre that had taken place, and was still occurring around the mountain during October, when any civilians straying onto the mountains were killed by the 16 SS.

I was with a patrol to cover San Giovanni (di Sopra and di Sotto). Two isolated houses between La Quercia and San Mantino. When we were near San Giovanni we could see tall men around di Sopra. We thought they looked like tall Germans. We crawled in the long grass to a part below di Sotto, when suddenly, a German appeared in the doorway. We were hiding the the long grass, and could see the German soldier had the “SS” emblem on his tunic. We knew the SS did not take prisoners, so we kept very still.

The SS soldier slowly turned, and went back into the house. We then started to return to battalion headquarters to report that di Sopra and di Sotto were occupied by the SS. As we started to return along the footpath, about a dozen men were rushing up the path towards. The officer thought they were Germans, and gave the order “every man for himself”. A sergeant and I ran down towards the ravine and stream (rio) and we ran through German bunker positions. None of the Germans fired their muskets at us. We were wearing soft woollen patrol caps, so they did not recognise us.

We managed to slide down to the stream (rio) and got back to La Quercia and to near Monsumo. We reported that the officer and other men would be prisoners, but they had returned to battalion headquarters before us. The officer had told us the men were all very young Italians, who only wanted to get back to their Mommas and Poppas.

At that time, we did not know about the massacre (still in progress), so the officer let them proceed on their way. The would have gone into the SS area. Later, when I spoke to ex-Partisans, I was told that about a dozen bodies of young Italians had been found just below Casaglia cemetery.

I still think during nights, if only (magari) we had known about the massacre, young lives could have been saved.

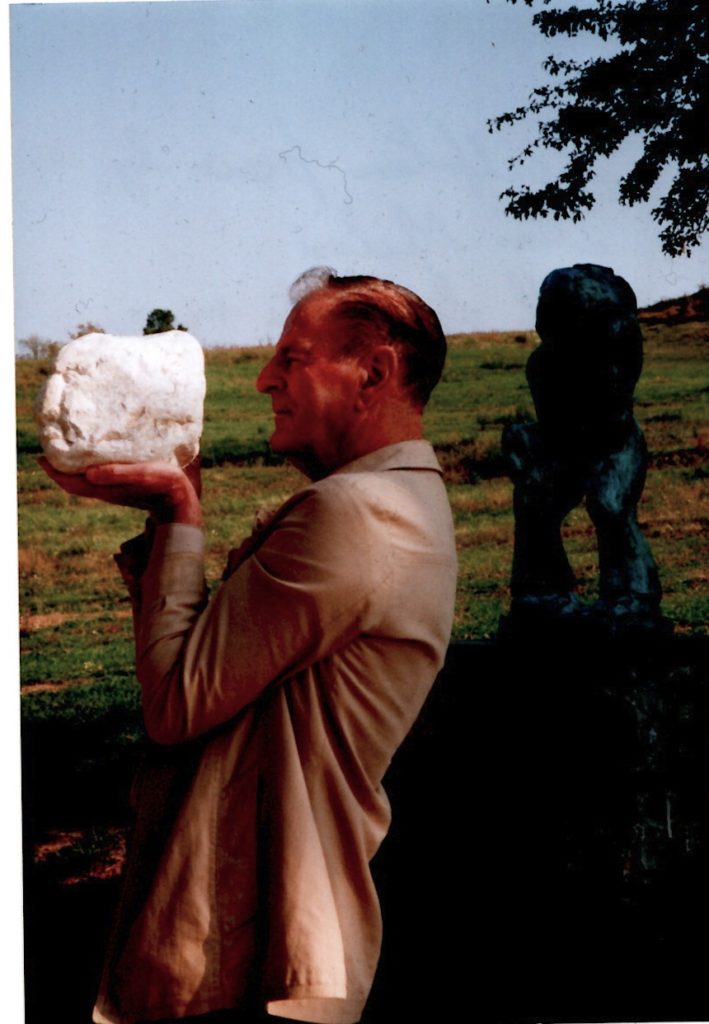

Philip Gourd with “Sculpture piece by Dino Milani with his Pieta in background, Monte Sole, Sept 1998”.

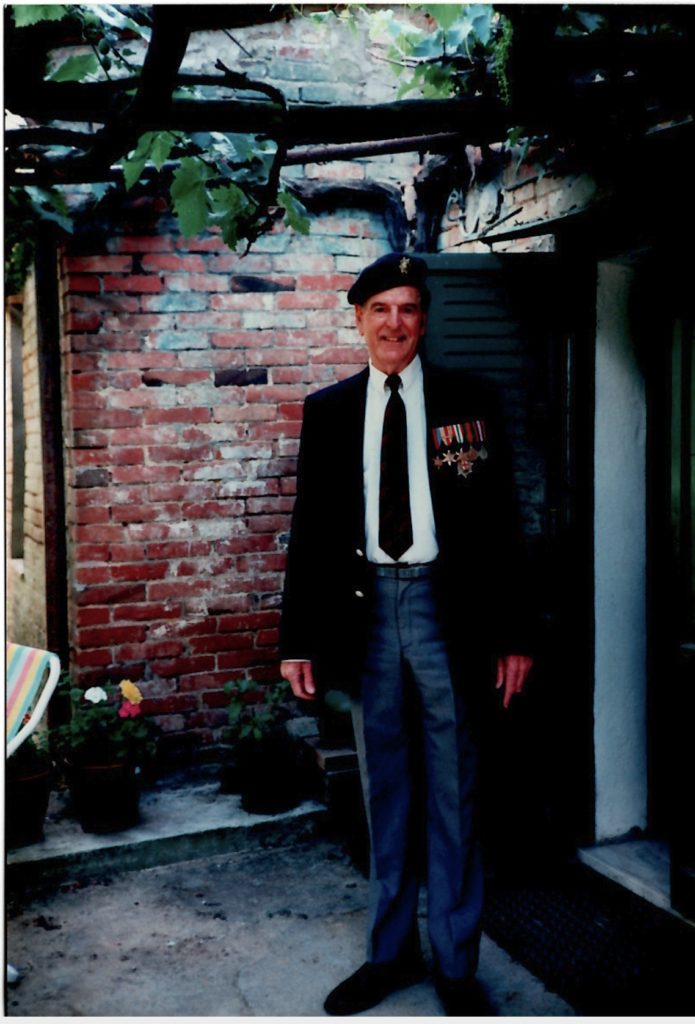

Philip Gourd with campaign medals 1990s

To hear more of Philip Gourd’s memories look here;

https://www.bishopsteigntonheritage.co.uk/people/bishopsteignton-audio-memories/